Greenwashing, along with its cousin, fairwashing refers to the practice of making dubious, or downright false environmental or ethical claims about a company’s products. In October and November of last year, it was found that the fashion sector has the highest proportion of “concerning claims”. This shouldn’t be a surprise to anyone, as in the past few years, a plethora of companies in both the fashion and jewellery industries have been established on the basis that they are more environmentally friendly and ethical. However, a cursory glance at some claims put forward by these companies reveal that their environmental and ethical claims are either nothing new or can easily be de-bunked. Below are six of the most dubious claims that are common amongst “eco-friendly” or “sustainable” jewellers, and why each of these claims is problematic.

1. Recycled Gold and Platinum

It’s no secret that mining is detrimental to the earth’s natural environment, thus recycled gold and platinum sounds like a great idea to protect our natural environment! However, there are a few problems with marketing gold and platinum as “recycled”:

- In a typical jewellery workshop, a lot of gold and platinum automatically gets recycled. Whether it be from filings, old jewellery brought in for re-modelling or metal left over from casting, a jewellery workshop typically sends about one third to one half of their gold and platinum holdings to a refiner to turn back into “new” gold or platinum that can be used to make jewellery. Thus, even without promoting the fact, all jewellers use at least some, if not a majority of “recycled” gold or platinum.

- A perecentage of recycled gold comes from stolen jewellery.

- Much like extracting pure gold from ore uses dangerous and harsh chemicals, the gold and platinum recycling process, aka refining also uses harsh chemicals, most notably hydrochloric and nitric acid. Refining jewellers waste (called lemel and sweeps) may also release toxic chemicals into the air as the waste in burnt off.

- Even if the jewellery industry used 100% recycled gold and platinum, it would have little to no effect on how much gold is mined. Because gold and platinum are both commodities, their value is more tied to the commodity market, than how much is used to create jewellery. If you consider that the gold price went from around US$300 per ounce in the 1990s, to over US$1500 per ounce in the 2010s, this point becomes even more clear, with gold and platinum price fluctuations, not due to demand, creating an eternal struggle for jewellers.

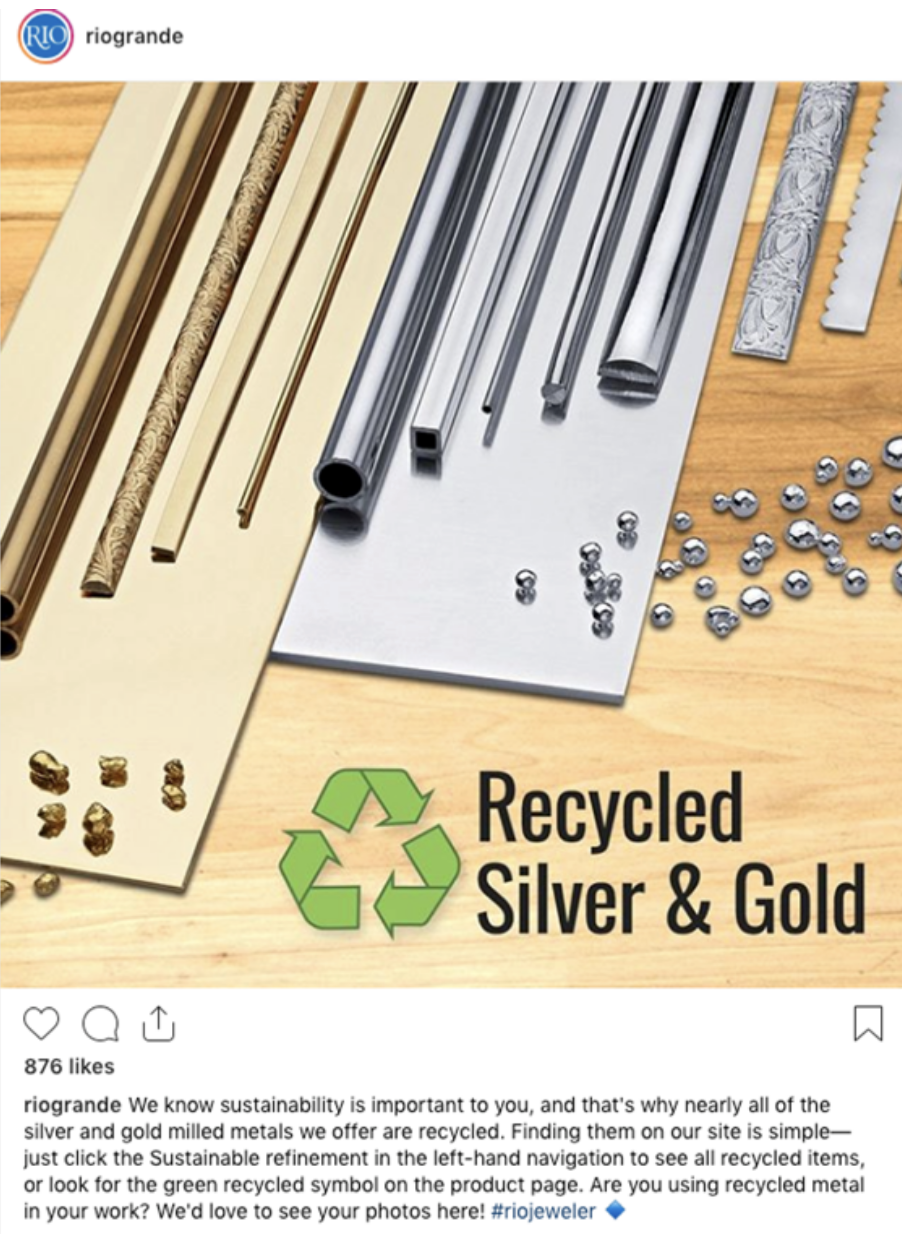

Above: American refinger Rio Grande promoting their recycled gold.

2. Digital Certificates

In 2022, GIA announced that their diamond dossier certificates, their most popular certificate and used mostly for diamonds under one carat, would no longer be paper based and thus digital only, accessible either through the GIA app or website from 1st January 2023. The problem with digital only certificates was that it made diamonds difficult to store and handle in many circumstances such as when they were waiting to be set into jewellery, waiting in a diamond wholesaler’s office to be picked up and even when shipping. In most cases, a disposable paper envelope was used in lieu of the paper certificate in order to make handling easier. Not to mention the fact that many consumers liked the small piece of paper that came with such an expensive purchase. GIA reversed their decision earlier this month, but one must wonder how on earth they thought this was a good idea.

3. Kimberley Process and The Responsible Jewellery Council

Established in 2003, The Kimberley Process was meant to tackle the issue of blood diamonds. However, whilst it may have been a step in the right direction, it is not without its flaws. As David Rhode, wrote in The Guardian, The Kimberley Process has a narrow focus, which is stopping diamonds from funding rebel movements, whilst ignoring other issues such as worker exploitation, and secondly, only batches of rough diamonds are certified, thus making it easy for non-certified diamonds to be smuggled inside certified batches.

Likewise, The Responsible Jewellery Council (RJC) was established in 2005 to promote ethical sourcing. However, as Kyle Abram writes, the RJC is more concerned about “underpinning trust”, rather than cleaning up the supply chain. In addition this, the RJC faced backlash over their decision no to suspend Russia’s one-third government owned diamond miner, Alrosa, leading to their executive director resigning.

4. Lab Grown Diamonds

Lab grown diamonds are touted by many of their sellers as “eco-friendly”, due to the fact that they are not dug out of the ground. However, lab grown diamonds are certainly not “mining free” as some would lead you to believe. This is because growing diamonds in a lab, depending on the process used, requires either graphite or high-purity methane and hydrogen – all of which are dug or drilled from the earth. Add this to the fossil fuels or rare earth metals in the solar panels used to generate the electricity for a diamond to be grown in a lab, and a more accurate picture of the environmental impact of a lab grown diamond can be drawn. Admittedly, this environmental impact may be small, however, there are many diamond mines that claim to be sustainable.

5. Sustainable Packaging

Many greenwashing jewellery companies espouse that their packaging is sustainable. In fact, even Tiffany has got on board the sustainable packaging bandwagon. However, much like the zero waste movement, marketing your packaging as sustainable, whilst it may be a positive move, completely ignores the waste generated by the supply chain. The fact that not many people outside the diamond and jewellery industry realise is that the industry, relative to the product we sell, is one of the biggest culprits of packaging waste. This is because diamonds and jewellery, being high value, need a large amount of packaging when being shipped. The theory being that the bigger and heavier the package is, and the more packaging it is wrapped in, the safer and more secure it will be. This of course leads to a huge amount of packaging waste from merely transporting diamonds and jewellery. For companies to then turn around and say their packaging is sustainable is the ultimate hypocrisy.

Above: Double boxing is the norm for shipping diamonds and jewellery, but not sustainable.

6. Diamond Origin

Over the past 20 or so years, diamond origin has become somewhat of a focal point, especially since the diamond industry drifts from one seemingly existential crisis to another – whether it be funding wars, to evil dictators in Zimbabwe or Russia. Many diamond companies market their diamonds as being from sustainable and/or ethical sources. However, upon examining many of these companies’ claims, they typically only focus on where their diamonds are mined, and not cut and polished, which in most cases is India. Whilst I am not suggesting that Indian manufacturers are doing anything ill toward, it seems to be something quite big to leave out if you are trying to market your supply chain as ethical and sustainable, especially given the problems the diamond industry in India has had regarding child labour.

Above: A map from Brilliant Earth of where their diamonds come from. India is not mentioned, despite being key in the supply chain.

Whilst the diamond and jewellery industry certainly isn’t perfect, the past 25 years has seen a lot of positive environmental and ethical changes, mostly I would say due to media attention. However, it is unfortunate that some companies make dubious environmental and ethical claims in order to spark emotion from consumers, when in fact their claims either have little impact on the environment or omit other key details about the supply chain. My advice to consumers, whether buying diamonds or any other consumer good, would be to thoroughly analyse any environmental or ethical claim, as many are complete rubbish.