Earlier this year, Jeweller Magazine published a complete anthology detailing the “fall from grace” of The Jewellers Association of Australia (JAA). As the article states, the decline of the JAA started almost a decade ago, seemingly caused by their own stupidity, which included promoting overseas diamond wholesalers over Australian wholesalers and attempting to launch their own rival trade fair in competition to one that had been running for 25 years.

Whilst I’ve only been in the industry for a little over 15 years, I’ve always thought the JAA was “all talk no action”. I am sure the JAA at some point was once an organisation that represented the majority of the industry and did the job well. Established in 1931, at one point, the JAA have claimed that they represented over 75 per cent of the industry. This would have been a lot easier in say the 1980s and 1990s than it is today, as pre-2000s, the local manufacturing industry was thriving, thanks in part to tax and tariff protections. This created a relative vacuum, where most jewellers knew everyone else, and compared to today, the jewellery offered was very homogenous.

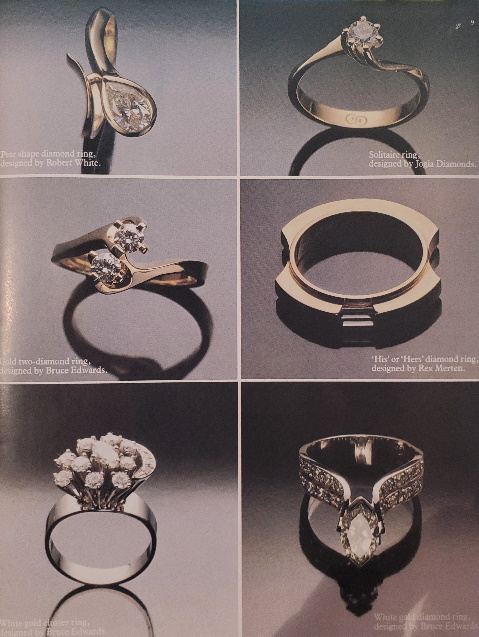

Above: A sample of the typical 1980s jewellery catalogue.

However, in the past 20 years, a lot has changed that has fractured the industry.

The popularisation of the internet in the mid to late 1990s had a profound effect on the industry. All of a sudden, consumers could buy jewellery online from jewellers in another state, or even another country. Likewise, retailers could connect with thousands of suppliers overseas without going on “buying trips” (aka junkets) with just a click of a mouse. With supply chains shortened and overheads potentially slashed, both traditional brick and mortar retailers and wholesalers were up in arms. A lot of people in the industry thought of online jewellery vendors as the anti-Christ. And that’s when the scare campaigns started. As the narrative went, buying jewellery online, no matter what the quality of the finished product was risky, and most likely to end up in regret. Funnily enough, online diamond dealers were largely responsible for making certified diamonds, especially GIA certified diamonds, so popular today – a move that eliminated mostly dodgy grading by so-called “valuers” that was so prevalent 20 years ago.

Next came the “diamond certification” war of the mid-to-late 2000s. Essentially, at the epicentre of this was DCLA, trying to spruik their certification services as somehow “internationally recognised”, whilst bad-mouthing everyone else in the Australian diamond industry. They did this through regular Today Tonight segments, of which I was once a part of, and even had a Press Council complaint upheld against them. Looking back on times, since we sold GIA certified diamonds 99% of the time, watching the industry in-fighting and even DCLA’s implosion was almost comical. The good news is that GIA is now universally accepted, not just in Australia, but around the world as the gold standard for diamond certification.

Thirdly, around 2012, in response to customer demand, we started designing jewellery using computer aided design (CAD). Although we were a little late to the party, it was around that time that CAD really started to take off in the jewellery industry. The uproar that CAD created was very similar to the uproar that Uber created when it first burst onto the scene. Essentially, traditional bench jewellers were the “taxi drivers” arguing against a new technology that was both customer friendly and potentially cheaper for the customer. Nowadays, speaking to many in the industry, CAD/CAM is the dominant method of manufacturing jewellery, whilst like The Amish, hobbyists and a few “rusted on” handmade jewellers resist technological change.

So, with a large proportion of the industry fracturing in front of it, the JAA, rather than trying to unite the industry, has, over the past 10 years, divided it even further. This has resulted in massive financial and membership losses for the JAA over the past few years.

As of the time of writing, the JAA listed 446 businesses as members on its website. IbisWorld claims there are nearly 4,000 jewellery businesses in Australia. This means the JAA now represents just 11% of the industry. With such as small base, it is beggars’ belief that the JAA still exists, and that they claim to represent the entire industry. To add insult to injury, just 52% of the industry, including JAA members, believe the JAA is recognised and respected for excellence and trusted leadership.

Above: Despite what the JAA does, JAA members are literally running away from the association.

With the JAA in such a weak position, it is surely time to ask the following questions:

- Do we need the JAA to lobby the government on behalf of the jewellery industry? No, as import duties for diamonds and jewellery are so low, any changes to these protections would not have much of an impact. In addition to this, being such a small organisation, it is hardly able to lobby government on bigger picture issues such as tax and training.

- Does the JAA effectively promote the jewellery industry? No, apart from its website, Facebook page and biennial jewellery design awards, the JAA does not promote the jewellery industry. In fact, I doubt few jewellery consumers nowadays would know the JAA exists.

- Is there any legislative requirements or training provided by the JAA? No, unlike professions such as law or accounting, there is need to join a professional association, nor is there any regulation of the jewellery industry. Likewise, the JAA does not provide any industry training which is provided largely by private organisations, TAFE and apprenticeships.

It is therefore time to ask the real question – “Do we really need the JAA”, or is it just a fragment of the past? If it is any consolation other industry associations such as the AMA are in a similar decline.